This a guest blog post featuring OpenStreetMap community member and OSM US board member, Brian Sperlongano. Do you have a story to tell? OpenStreetMap US news or info to share? Message us at team@openstreetmap.us and we’ll work with you to craft a blog post to share with the community!

We started building OpenStreetMap Americana with the idea of a map that looks and feels familiar to Americans. However, the United States is a diverse place, with millions of people speaking a language other than English at home. Besides English, the U.S. is home to more than a million speakers each of Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Arabic, French, and Korean.

Thanks to the hard work of the project’s volunteer contributors, OSM Americana is now accessible to people speaking a broad range of languages. Instead of English-language names, the map renders language-appropriate labels based on the user’s web browser settings, thanks to vector tile and Wikidata technology.

I love exploring new places by looking at maps. While it’s fascinating to see maps of faraway places in interesting, exotic languages and scripts, it’s not very useful to me when I see the Chinese capital labelled 北京市 on the map! I need the map to say “Beijing.” However, my Chinese friend Jìng would expect to see the Chinese capital rendered in Chinese, and further, would expect New York City to be labelled 纽约!

The fact that different languages and language scripts are in use worldwide is a challenge for a global digital map. For raster maps, such as the standard tile layer on openstreetmap.org, the map is a grid of server-generated images. That means the cartographer must decide what labels to draw on the map ahead of time. There are two basic approaches:

- Use a single language

- Use the local language

Since the standard tile layer is a raster map, rendered on the server, it shows place labels in whatever the local language is – thus New York is New York, Beijing is 北京市, Seoul is 서울, and Kathmandu is काठमाडौं. As an American looking at a map in non-English-speaking areas, the map sure is interesting! However, I would have to hunt for Osaka on this map:

(c) OpenStreetMap Contributors (location)

Since OpenStreetMap Americana is based on vector tile technology, we can scrap fixed labels entirely and customize what’s shown to the user. Dynamic labels are possible because the server encodes language information in the vector tiles it sends to the user’s web browser. Then, a bit of JavaScript determines which language the user has configured in their web browser and chooses the most appropriate label.

A Japanese user viewing a map of the United States might see something like this:

© OpenStreetMap Contributors (location)

That’s pretty neat but insufficient if our user speaks multiple languages or a location doesn’t have a name available in the desired language.

Meet my friend Keiko from Japan!

- As a native speaker of Japanese, Keiko would prefer to see a Japanese label if it’s available.

- Like most Japanese people, Keiko studied English for six years in school, so if a Japanese label is unavailable, she would like to see an English label.

- Keiko has just moved to Italy, and she’s starting to learn Italian. If neither Japanese nor English is available, she would prefer to see a label in Italian.

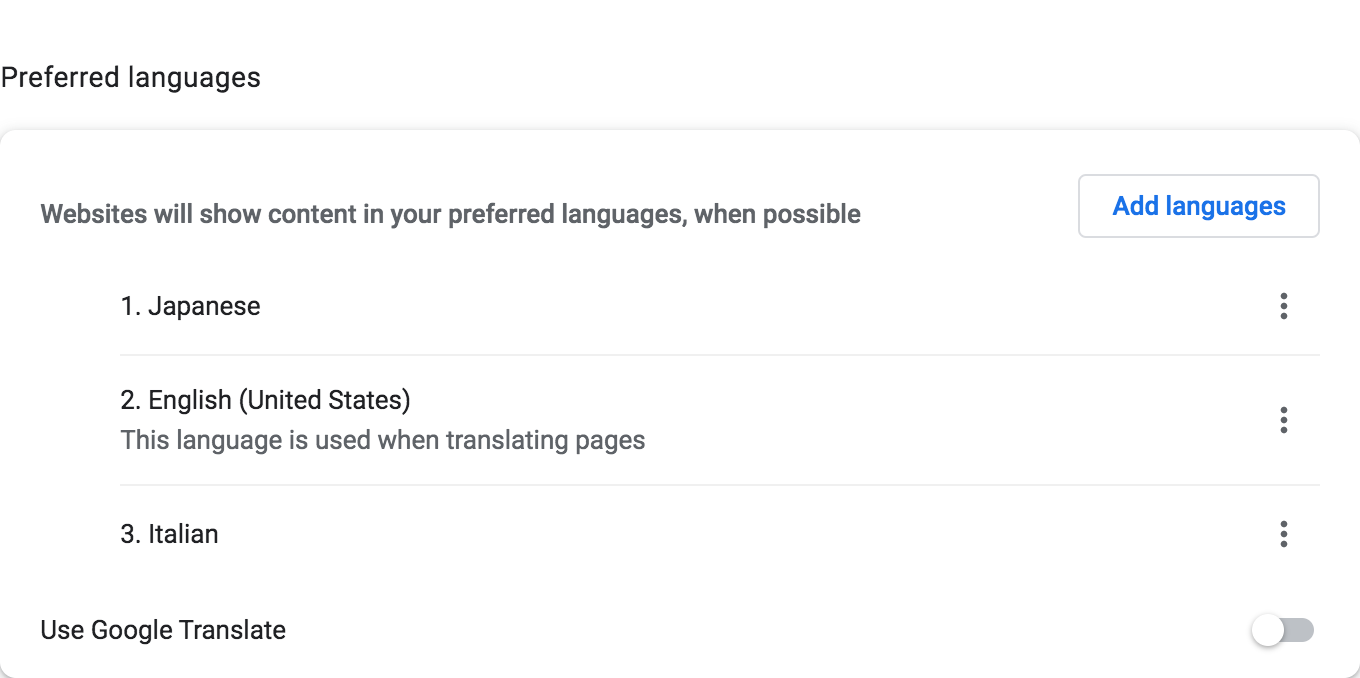

Keiko’s Google Chrome settings might look like this:

Using these rules, Keiko would like to check out a map of the Naples area. But Naples lacks a name:ja tag, which would typically indicate the city’s name in Japanese. Fortunately, it is tagged wikidata=Q2634, which refers to the item about Naples on Wikidata, Wikipedia’s companion knowledge graph project. OSM Americana’s OpenMapTiles-based vector tiles fall back to the Japanese label in this Wikidata item, resulting in ナポリ on the map:

© OpenStreetMap Contributors (location)

Towering over the city of Naples is the volcano Vesuvius, located in Vesuvius National Park. That park is mapped with a boundary relation, and it has no language-specific names tagged, having only the local Italian name=Parco Nazionale del Vesuvio, along with wikidata=Q635414. In addition, the Wikidata item lacks a Japanese name, but it does have an English one, which is shown on the map.

Lastly, just offshore is the Kingdom of Neptune Marine Protected Area, also represented by a boundary relation and a Wikidata item, however, all name entries in either location are listed in Italian only. Thus, the map falls back to the local-language label: “Area marina protetta Regno di Nettuno.”

Even better, for major cities, we can render the user’s preferred language label, with the local language label shown beneath. This gives the user the best of both worlds: a readable, memorable name alongside a name they’ll see posted on the ground – at the same time.

With this new rendering rule, we’ve created something very exciting – Keiko can see her native Japanese along with the local Italian:

© OpenStreetMap Contributors (location)

We invite you to take OSM Americana for a test drive! Explore the live global map. How does the map look in your languages of choice? Are translated place names missing in your area? If so, you can add the missing information to Wikidata or OSM! OSM Americana uses a combination of Wikidata entries and OSM name:xx tags.

With vector tile technology, integration of open databases like OpenStreetMap and Wikidata, and a vibrant open source community of like-minded map enthusiasts, we can create great and accessible things together. Contributions are welcome at the project’s GitHub repository, or chat with the team on the OpenStreetMap U.S. Slack workspace’s #americana-map-style channel.

OpenStreetMap Americana is a community map style developed by members of the U.S. mapping community dedicated to open-source, North American–influenced cartography. For more detail about this style, check out the recording of the American Map Style presentation at State of the Map US 2022.

Wikidata is a free and open knowledge base that can be read and edited by both humans and machines.

Both OpenStreetMap Americana and Wikidata are published under a Creative Commons CC0 waiver, which dedicates both works to the public domain.

OpenStreetMap® is open data, licensed under the ODbL by the OpenStreetMap Foundation.